Acute Myocardial Infarction

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is the medical term for a heart attack and occurs when a blood clot forms around plaque in the arteries, blocking supply of blood to the heart [1]. Approximately 200 heart attacks per 100,000 adults over the age of 20 occur in Canada each year [2]. AMI risk is primarily attributed to lifestyle factors including smoking, poor diet, alcohol consumption, obesity, physical inactivity, and recreational drug use [3]. Evidence for occupational risk factors for AMI are inconsistent, but certain occupations have been associated with higher cardiovascular risk [4].

Possible occupational risk factors [5-10]

-

- Noise

- Vibrations

- Temperature extremes

- Secondhand smoke

- Shift work

- Occupational physical activity

- Chemical and particulate hazards

- Psychosocial stress

Key Findings

Almost 25,000 cases of AMI were diagnosed among workers in the ODSS between 2007 and 2016. Increased AMI risk was associated with employment in a large variety of occupation groups in the ODSS. This reflects the variety of possible occupational risk factors. Future studies are necessary to examine which work-related hazards might be contributing to these excess risks.

In general, AMI risk was higher among blue-collar workers compared to white-collar workers, and the most consistently elevated risks were observed for workers in industry and occupation groups related to logging and wood production and mining with increased risks observed for some construction sector and textile processing groups.

Despite exposure to psychosocial stress and shiftwork, employment in some protective services occupations including firefighting and police was associated with reduced risk of AMI. The reduced risk observed for these workers may reflect the stringent health-related requirements enforced across these occupations. Another factor may be that workers with an accepted claim for compensation related to AMI were excluded from this analysis, so the association estimated by our approach may underestimate the true risk.

Wood-related industries and occupations

The most consistent excess risks for AMI in the ODSS cohort were for workers in industry and occupations groups related to wood and wood processing. These workers may be exposed to a variety of AMI risk factors including noise, stress and vibrations. Inhalation of wood dusts may cause irritation and inflammatory responses that could contribute to cardiovascular disease [11]. An increased risk of AMI associated with high noise exposure has been seen in BC sawmill workers [9]. An increased risk of AMI has also been observed among a cohort of Swedish pulp and paper mill workers [12], and attributed to a combination of workplace exposures including dust, sulfur compounds, shiftwork and noise.

Forestry and logging

-

- Forestry industry: 1.38 times the risk

- Logging: 1.37 times the risk

- Forestry services: 1.55 times the risk

- Forestry and logging occupations: 1.35 times the risk

- Log hoisting, sorting, moving and related: 1.75 times the risk

- Timber cutting and related: 1.28 times the risk

- Forestry industry: 1.38 times the risk

Wood products

-

- Wood manufacturing industries: 1.27 times the risk

- Wooden box factories: 1.56 times the risk

- Veneer and plywood mills: 1.41 times the risk

- Sawmills, planning mills and shingle mills: 1.32 times the risk

- Sash, door and other millwork plans: 1.26 times the risk

- Wood processing occupations: 1.49 times the risk

- Inspecting, testing, grading and sampling: 1.81 times the risk

- Occupations in labouring and other elemental work: 1.73 times the risk

- Other wood processing occupations, nec: 1.50 times the risk

- Wood manufacturing industries: 1.27 times the risk

Pulp and paper

-

- Pulp and papermaking and related occupations: 1.30 times the risk

- Cellulose pulp preparing: 2.25 times the risk

- Pulp and papermaking and related occupations: 1.30 times the risk

Mining and quarrying

Increased risks for acute myocardial infarction and other cardiovascular disease have been previously observed for mining industry workers, with potential links to exposure to high levels of noise [13,14], vibration [15] and radon gas, particularly for uranium mining workers [16]. Diesel engine exhaust, a common exposure in mining, is also a potential cause of acute cardiovascular events [17]. While elevated risks were observed for some mining industry workers, risks among mining and quarrying occupations groups were generally only slightly increased.

-

- Quarries and sand pits industry: 1.40 times the risk

- Sand pits and quarries: 1.57 times the risk

- Metal mine industry: 1.12 times the risk

- Gold quartz mines: 1.53 times the risk

- Uranium mines: 1.39 times the risk

- Quarries and sand pits industry: 1.40 times the risk

Construction

Construction workers are exposed to loud noise [18] and vibrations in their work. Construction workers can also be exposed to crystalline silica dust and diesel engine exhaust. In the ODSS, increased risk of AMI was greatest among workers involved in excavating, grading and paving, who are exposure to a variety of occupational risk factors for AMI.

-

- Occupations in labouring and other elemental work: excavating, grading and paving: 1.41 times the risk

- Excavating, grading and related occupations: 1.31 times the risk

Textile manufacturing and processing

Increased risk of AMI was observed for workers employed in the leather and textile manufacturing industries and related occupations. Evidence regarding AMI risk factors for these workers is limited, but textile dust exposures [19] and exposure to bacterial endotoxin [20] have been previously suggested.

-

- Textile fibre preparing occupations: 2.65 times the risk

- Shoemaking and repairing occupations: 1.74 times the risk

- Occupations in labouring and other elemental work, fabricating, assembling and repairing, textile, fur and leather products: 1.44 times the risk

- Fabricating, assembling and repairing occupations, textile, fur and leather products: 1.44 times the risk

- Leather industries: 1.48 times the risk

- Luggage, handbag and small leather goods manufacturers: 1.55 times the risk

- Shoe factories: 1.48 times the risk

- Leather tanneries: 1.44 times the risk

- Textile industries: 1.16 times the risk

- Automobile fabric accessories: 1.46 times the risk

- Man-made fibre, yarn and cloth mills: 1.43 times the risk

Rubber and plastics manufacturing

Increased AMI risk was observed among workers in the ODSS employed in rubber and plastic products fabrication. Plastic stabilizers frequently include cadmium, which has been posited to increase AMI risk through atherosclerosis [21]. A cohort study of British rubber factory workers found increased risk of cardiovascular deaths associated with exposure to N-nitrosomorpholine, rubber dust, rubber fumes and N-nitrosamines sum [22].

-

- Occupations in labouring and other elemental work: fabricating, assembling and repairing, rubber, plastic and related products: 1.91 times the risk

- Bonding and cementing occupations, rubber, plastic and related products: 1.40 times the risk

Other groups

Excess AMI risk was detected in the ODSS for a variety of occupation groups, which likely reflects the numerous risk factors for cardiovascular disease including both workplace and lifestyle factors.

-

- Receptionists and information clerks: 1.62 times the risk

- Fish canning, curing and packing occupations: 1.52 times the risk

- Truck drivers: 1.32 times the risk

For more details: Troke, N, Logar‐Henderson, C, DeBono, N, et al. Incidence of acute myocardial infarction in the workforce: findings from the Occupational Disease Surveillance System. Am J Ind Med. 2021; 1– 20.

Relative Risk by Industry and Occupation

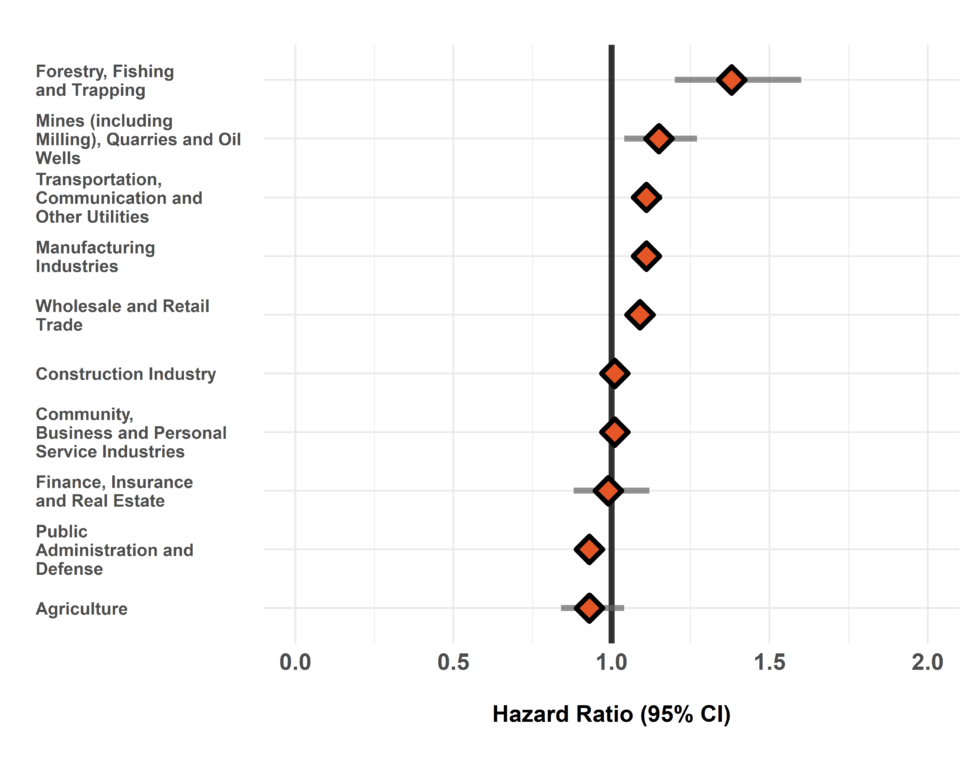

Figure 1. Risk of acute myocardial infarction diagnosis among workers employed in each industry group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1983-2016

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

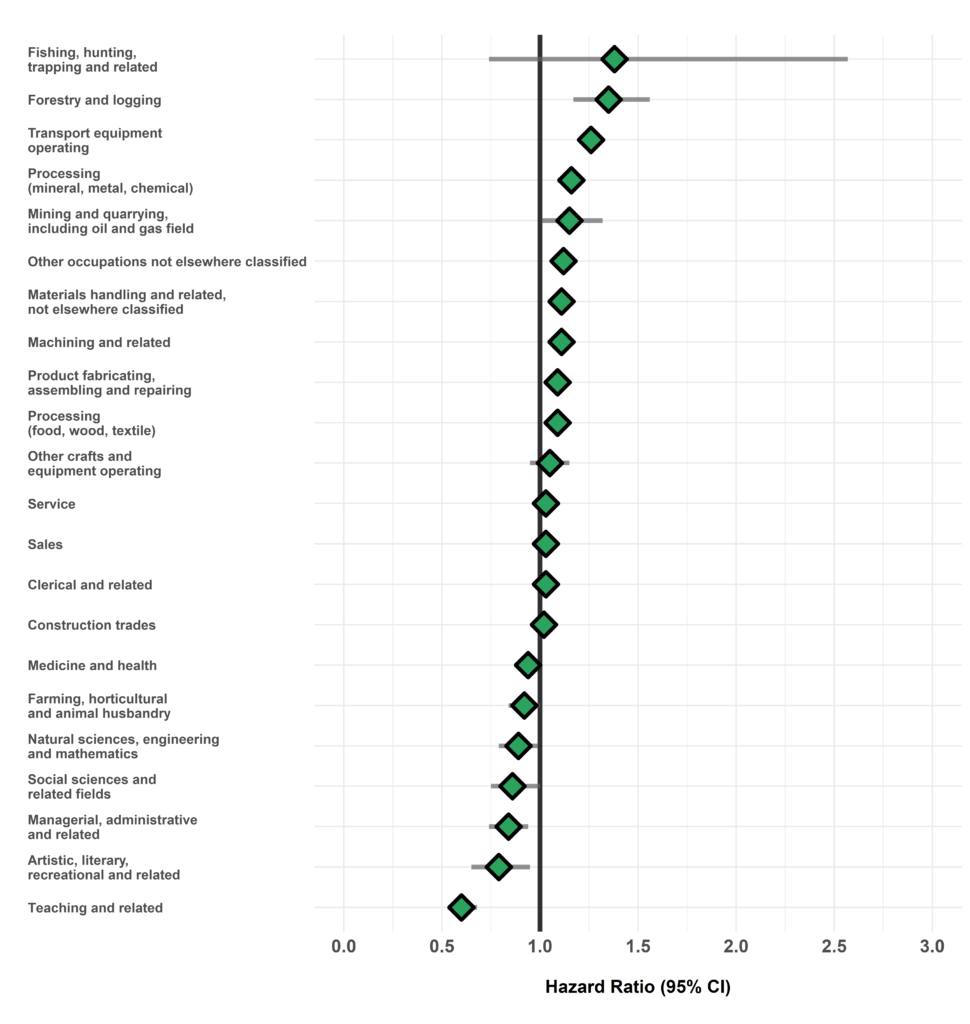

Figure 2. Risk of acute myocardial infarction diagnosis among workers employed in each occupation group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1983-2016

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

Table of Results

| SIC Code * | Industry Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 1 | Agriculture | 339 | 24904 | 0.93 (0.84-1.04) |

| 2/3 | Forestry, Fishing and Trapping | 190 | 6468 | 1.38 (1.20-1.60)*** |

| 4 | Mines, Quarries and Oil Wells | 376 | 13707 | 1.15 (1.04-1.27)** |

| 5 | Manufacturing | 9589 | 473168 | 1.11 (1.09-1.14)*** |

| 6 | Construction | 2781 | 151153 | 1.01 (0.97-1.05) |

| 7 | Transportation, Communication and Other Utilities | 3044 | 143012 | 1.11 (1.07-1.16)*** |

| 8 | Trade | 5045 | 317800 | 1.09 (1.05-1.12)*** |

| 9 | Finance, Insurance and Real Estate | 256 | 15688 | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) |

| 10 | Community, Business and Personal Service | 4928 | 421561 | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) |

| 11 | Public Administration and Defense | 2112 | 132668 | 0.93 (0.89-0.97)*** |

| * SIC: Standard Industrial Classification (1970) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

Table 2. Surveillance of Acute Myocardial Infarction: Number of cases, workers employed, and hazard ratios in each occupation (CCDO) group

| CCDO Code * | Occupation Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 11 | Managerial, administrative and related | 275 | 23568 | 0.84 (0.74-0.94)** |

| 21 | Natural sciences, engineering and mathematics | 329 | 20218 | 0.89 (0.79-0.99)* |

| 23 | Social sciences and related fields | 192 | 23146 | 0.86 (0.75-1.00)* |

| 25 | Religion | <5 | 83 | — |

| 27 | Teaching and related | 237 | 36802 | 0.60 (0.53-0.68)*** |

| 31 | Medicine and health | 837 | 95161 | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) |

| 33 | Artistic, literary, recreational and related | 111 | 11744 | 0.79 (0.65-0.95)* |

| 41 | Clerical and related | 2073 | 141042 | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) |

| 51 | Sales | 1265 | 110656 | 1.03 (0.97-1.09) |

| 61 | Service | 3395 | 253769 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) |

| 71 | Farming, horticultural and animal husbandry | 489 | 36677 | 0.92 (0.84-1.00) |

| 73 | Fishing, hunting, trapping and related | 10 | 373 | 1.38 (0.74-2.57) |

| 75 | Forestry and logging | 181 | 6474 | 1.35 (1.17-1.56)*** |

| 77 | Mining and quarrying, including oil and gas field | 211 | 7722 | 1.15 (1.01-1.32)* |

| 81 | Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) | 1263 | 58540 | 1.16 (1.09-1.22)*** |

| 82 | Processing (food, wood, textile) | 1247 | 70950 | 1.09 (1.03-1.15)** |

| 83 | Machining and related | 3123 | 137820 | 1.11 (1.07-1.15)*** |

| 85 | Product fabricating, assembling and repairing | 4930 | 233837 | 1.09 (1.05-1.12)*** |

| 87 | Construction trades | 3108 | 152813 | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) |

| 91 | Transport equipment operating | 3116 | 122651 | 1.26 (1.21-1.30)*** |

| 93 | Materials handling and related, not elsewhere classified | 2158 | 111390 | 1.11 (1.06-1.16)*** |

| 95 | Other crafts and equipment operating | 416 | 19357 | 1.05 (0.95-1.15) |

| 99 | Other occupations not elsewhere classified | 2954 | 157206 | 1.12 (1.08-1.17)*** |

| * CCDO: Canadian Classification Dictionary of Occupations (1971) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

References

- University of Ottawa Heart Institute. Heart Attack [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.ottawaheart.ca/heart-condition/heart-attack.

- Government of Canada. Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)- Acute Myocardial Infarction [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 7]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/

- Heart&Stroke. Heart Attack [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.heartandstroke.ca/heart-disease/conditions/heart-attack

- Nowrouzi-Kia B, Li AKC, Nguyen C, Casole J. Heart Disease and Occupational Risk Factors in the Canadian Population: An Exploratory Study Using the Canadian Community Health Survey. Saf Health Work [Internet]. 2018;9(2):144–8.

- Steenland K. Epidemiology of occupation and coronary heart disease: Research agenda. Am J Ind Med [Internet]. 1996

- Hlatky MA, Lam LC, Lee KL, Clapp-Channing NE, Williams RB, Pryor DB, et al. Job strain and the prevalence and outcome of coronary artery disease. Circulation [Internet]. 1995;92(3):327–33.

- van Kempen EEMM, Kruize H, Boshuizen HC, Ameling CB, Statsen BAM, de Hollander AEM. The association between noise exposure and blood pressure and ischemic heart disease: A meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2002;110(3):307–17.

- Wang XS, Armstrong MEG, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC. Shift work and chronic disease: The epidemiological evidence [Internet]. Occupational Medicine. 2011.

- Davies HW, Teschke K, Kennedy SM, Hodgson MR, Hertzman C, Demers PA. Occupational exposure to noise and mortality from acute myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2005;16(1):25–32.

- Krause N. Physical activity and cardiovascular mortality – Disentangling the roles of work, fitness, and leisure [Internet]. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health. 2010.

- WHO/SDE/OEH/99.14. Hazard Prevention and Control in the Work Environment: Airborne Dust. In.

- Andersson E, Persson B, Bryngelsson IL, Magnuson A, Torén K, Wingren G, et al. Cohort mortality study of Swedish pulp and paper mill workers – Nonmalignant diseases. Scand J Work Environ Heal [Internet]. 2007;33(6):470–8.

- Liu J, Xu M, Ding L, Zhang H, Pan L, Liu Q, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and noise-induced hearing loss in Chinese coal miners. J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2016;8(3):422–9.

- Li X, Dong Q, Wang B, Song H, Wang S, Zhu B. The Influence of Occupational Noise Exposure on Cardiovascular and Hearing Conditions among Industrial Workers. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2019;9(1):1–7.

- Björ B, Burström L, Eriksson K, Jonsson H, Nathanaelsson L, Nilsson T. Mortality from myocardial infarction in relation to exposure to vibration and dust among a cohort of iron-ore miners in Sweden. Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 2010;67(3):154–8.

- Rashida VJM al, Wang X, Myers OB, Boyce TW, Kocher E, Moreno M, et al. Greater Odds for Angina in Uranium Miners Than Nonuranium Miners in New Mexico. J Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 2019;61(1):1–7.

- Cosselman KE, Allen J, Jansen KL, Stapleton P, Trenga CA, Larson T V., et al. Acute exposure to traffic-related air pollution alters antioxidant status in healthy adults. Environ Res [Internet]. 2020;

- Pettersson H, Olsson D, Järvholm B. Occupational exposure to noise and cold environment and the risk of death due to myocardial infarction and stroke. Int Arch Occup Environ Health [Internet]. 2020;93(5):571–5.

- Wiebert P, Lönn M, Fremling K, Feychting M, Sjögren B, Nise G, et al. Occupational exposure to particles and incidence of acute myocardial infarction and other ischaemic heart disease. Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 2012;69(9):651–7.

- Stoll LL, Denning GM, Weintraub NL. Potential role of endotoxin as a proinflammatory mediator of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol [Internet]. 2004;24(12):2227–36.

- Messner B, Knoflach M, Seubert A, Ritsch A, Pfaller K, Henderson B, et al. Cadmium is a novel and independent risk factor for early atherosclerosis mechanisms and in vivo relevance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol [Internet]. 2009;29(9):1392–8.

- Hidajat M, McElvenny DM, Ritchie P, Darnton A, Mueller W, Agius RM, et al. Lifetime cumulative exposure to rubber dust, fumes and N-nitrosamines and non-cancer mortality: A 49-year follow-up of UK rubber factory workers. Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 2020;77(5):316–23.