Male Breast Cancer: A Key to Understanding Occupational Risks of Breast Cancer?

Background

Approximately 200 men are diagnosed with breast cancer each year in Canada, accounting for less than 1% of breast cancer cases [1-3]. Due to the lack of screening and early detection for male breast cancer, cases are often diagnosed at a later stage than in females, leading to poorer survival [4]. There are many well established risk factors for female breast cancer such as family history of breast cancer, BRCA genetic mutations, reproductive history (e.g. late menopause, late or no pregnancies), use of contraceptives or hormonal therapy, ionizing radiation exposure, obesity, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, and higher socioeconomic status [2, 5-6]. Some of these risk factors, such as higher socioeconomic status, reproductive and hormonal factors (e.g. parity, use of contraceptives) are more common in working women, often masking the role that occupation plays in the risk of breast cancer [7]. Less is known about male breast cancer because it is rare, but it does share some risk factors with female breast cancer such as family history of breast cancer, BRCA genetic mutations, obesity, hormonal imbalances, and ionizing radiation exposure [2, 5-6]. Studying male breast cancer risk provides an opportunity to learn about occupational risk factors for female breast cancer [8].

| Possible Occupational Risk Factors |

| Night shift work [6] |

| Endocrine disrupting compounds [9-10] |

| Ethylene oxide [6] |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHS) [9] |

| Organic solvents [11] |

| X- and gamma radiation [6, 9, 12] |

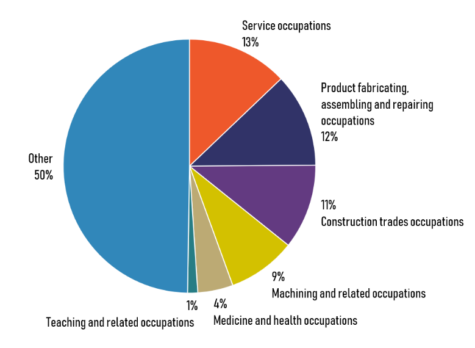

The Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS) provides the unique opportunity to examine both male and female breast cancer in a large cohort of workers, identifying 492 males and 17,865 females with breast cancer. Specific occupation groups in the ODSS with the greatest number of male breast cancer cases are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Percentage of male breast cancer cases by occupation group in the ODSS cohort.

Occupational Risks

The following results show the percent increase for male and female breast cancer risk among groups of workers in specific industry or occupation compared to all other workers followed in the ODSS.

Nursing and health

Previous studies have consistently shown increased breast cancer risk in female nurses and is often attributed to night shift work [6,9,11,13-14]. Similarly, increased risks for male and female breast cancer were observed in primarily nursing occupations in the ODSS. Shift work can lead to melatonin suppression, which has been reported as a risk for multiple cancers, including breast [15]. Shift work disrupts the circadian rhythm resulting in damaging effects on immune function and hormone balancing [9]. Studies have found no sex difference between night shift work and risk of cancer which further supports night shift work as a risk factor in both males and females [15-16]. Nurses may also be exposed to antineoplastic agents, which are hazardous drugs used to treat cancer and can cause damage to DNA [17]. Other medicine and health occupations also showed an increased risk of breast cancer, including medical laboratory and radiologic technologists. These workers may also be exposed to ionizing radiation, or ethylene oxide, a chemical used in the sterilization of medical and dental equipment, both have been associated to increased breast cancer risk [18-20].

| Industry or Occupation | Increased risk | |

| Males | Females | |

| Health and welfare services industry | 185%* | 8%* |

| Occupations in medicine and health | 383%* | 10%* |

| Nursing therapy and related assisting occupations | 373%* | 8%* |

| Nurses, registered, graduate and nurses-in-training | 738%* | 19%* |

| Nursing aides and orderlies occupation | 472%* | 6% |

| Other occupations in medicine and health | 550%* | 18%* |

| *Statistically significant (α=0.05) | ||

Education and related

Increased risks for male and female breast cancer were observed for education, teaching, social science, and clerical related occupations in the ODSS. Previous studies have reported increased breast cancer risk among women in professional occupations with no clear indication of what exposures are involved [21]. Findings may be related to sedentary behaviour and lack of physical activity. It is well established that physical activity is an important factor in breast cancer prevention, in lowering sex hormones and reducing adiposity and inflammation [22-23]. Both occupational and non-occupational physical activity have been shown to reduce breast cancer risk when compared to sedentary work habits [24]. Findings may also be related to increased stress in these occupations, however the evidence is sparse [25].

| Industry or Occupation | Increased risk | |

| Males | Females | |

| Education and Related Services Industry | 79%* | 21%* |

| Elementary and Secondary Schools Industry | 54%* | 19%* |

| Elementary and secondary school teaching occupations | 116%* | 27%* |

| Other teaching and related occupations | — | 25%* |

| Occupations in social sciences and related fields | 165%* | 14% |

| Clerical and related occupations | 45%* | 10%* |

| –case count <5; *Statistically significant (α=0.05) | ||

Other occupations

Other occupations with increased risk for male breast cancer include transport and equipment operating (133%) and food and beverage preparation service occupations (184%), possibly related to chemical exposures (e.g. organic solvents, PAHs) and shift work [5]. There were a higher number of male breast cancer cases among janitors and cleaners in the ODSS. Janitors and cleaners may be exposed to a variety of chemicals (e.g. acetone, formaldehyde, surfactants) and night shift work [5].

Risk Recognition

Breast cancer is influenced by a complex mix of factors and there continues to be limited understanding on the role of occupational risk factors. Given that increased risks of breast cancer was found in similar working groups for males and females in the ODSS, the effect of occupational risk factors should not be ignored. Further investigation in specific groups, such as service workers is needed. This can lead to better awareness of male breast cancer and help to understand and prevent specific risk factors involved in breast cancer.

References

- Cancer Care Ontario. 2019. Breast cancer.

- Canadian Cancer Society. (2021). Risks for breast cancer.

- Sritharan J, MacLeod JS, Dakouo M, Qadri M, McLeod CB, Peter A, & Demers PA. Breast cancer risk by occupation and industry in women and men: Results from the Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS). American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2019, 62:3, 205-211.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). List of Classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, IARC Monographs Volumes 1-127(2020).

- Akinyemiju TF, Pisu M, Waterbor JW & Altekruse SF. Socioeconomic status and incidence of breast cancer by hormone receptor subtype. Springerplus. 2015 Dec;4(1):1-8.

- Fenga C. Occupational exposure and risk of breast cancer (Review). Biomed Reports. 2016;4(3):282–92.

- Gray JM, Rasanayagam S, Engel C, Rizzo J. State of the evidence 2017: An update on the connection between breast cancer and the environment. Environmental Health 2017;16(1):1–61.

- Labrèche F, Kim J, Song C, Pahwa M, Ge CB, Arrandale VH, et al. The current burden of cancer attributable to occupational exposures in Canada. Prev Med. 2019;122:128–39.

- Weiss JR, Moysich KB, Swede H. Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Jan 1;14(1):20-6.

- Hansen J, Stevens RG. Case-control study of shift-work and breast cancer risk in Danish nurses: Impact of shift systems. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48:1722–1729.

- Lie JA, Andersen A, Kjaerheim K. Cancer risk among 43000 Norwegian nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health. 2007;33:66–73.

- Liu W, Zhou Z, Dong D, Sun L & Zhang G. Sex differences in the association between night shift work and the risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of 57 articles. Disease Markers, 2018, 7925219

- Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Lynge E, Gunnarsdottir HK, Sparen P, Tryggvadottir L, Weiderpass E & Kjaerheim K. Occupation and cancer – follow-up of 15 million people in five Nordic countries. Acta Oncol 2009;48(5):646-790.

- (2004). NIOSH alert: preventing occupational exposures to antineoplastic and other hazardous drugs in health care settings.

- Preston DL, Kitahara CM, Freedman DM, Sigurdson AJ, Simon SL, Little MP, Cahoon EK, Rajaraman P, Miller JS, Alexander BH, Doody MM & Linet MS. (2016). Breast cancer risk and protracted low-to-moderate dose occupational radiation exposure in the US radiologic technologists cohort, 1983-2008. British Journal of Cancer, 115(9): 1105-1112.

- Mohan AK, Hauptmann M, Freedman DM, Ron E, Matanoski GM, Lubin JH, Alexander BH, Boice JD Jr, Doody MM and Linet MS. (2003). Cancer and other causes of mortality among radiologic technologists in the United States. International Journal of Cancer , 103: 259-267.

- US National Toxicology Program. Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition: Ethylene oxide. 2016.

- Ji BT, Blair A, Shu, XO et al. Occupation and breast cancer risk among Shanghai women in a population-based cohort study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2008, 51(2): 100-110.

- Kruk J. (2009). Lifetime occupational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer P, 10(3): 443-448.

- Ekenga CC, Parks CG & Sandler DP. (2015). A prospective study of occupational physical activity and breast cancer risk. Cancer Cause Control, 26(12): 1779-1789.

- Chen X, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Xie Q & Tan X. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 38 cohort studies in 45 study reports. Value Health, 2019, 22(1): 104-128.

- Pudrovska T, Carr D, McFarland M & Collins C. (2013). Higher-status occupations and breast cancer: a life-course stress approach. Social Science & Medicine, 89: 53-61.

The Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS) Surveillance Alerts provide brief summaries of occupational exposures and disease risks across different industries and occupational groups. The aim of these alerts is to highlight new or emerging issues detected through occupational disease surveillance. At this time the ODSS includes workers from 1983-2014 and follows their health outcomes until 2016. This alert reflects only the diseases currently tracked within the ODSS. The system is updated and expanded on an ongoing basis.

More information about the ODSS including data sources, methods and detailed results can be found at ODSP-OCRC.ca and OccDiseaseStats.ca.